The Road to Tijuana

Alberto

Alberto [Note], from Honduras, watched his country fall to pieces over the last decade. For eight years he paid “rent” to the gang that rules his neighborhood, but last Fall the new leader demanded a sum three times more than he could put together. He begged but they threatened to kill his family one by one. Alberto hoped it was a bluff, until he came home around Christmas to find his wife beaten to death. He grabbed his six-year-old daughter, Susana, pocketed the last of their cash, and ran. Alberto and Susana took buses across Honduras and Guatemala, then hopped the train called “La Bestia” for the ride up the length of Mexico. The wait list to see an asylum officer at the border was six weeks, and the gang controlling the tent city outside Ciudad Juarez wanted to know what cash or services Alberto – or Susana – were offering to cover the cost of their stay. Alberto and Susana instead joined a group walking through the desert. They were picked up by Border Patrol and brought to a detention center near El Paso.

Alberto was put into a holding area with 125 other men, but the officer held Susana back. For her safety, he said, she would be taken to another camp nearby. Alberto spent the next three months in a variety of camps and prisons along the border. He was interviewed twice by Homeland Security agents and told his story as best he could. In May, however, he got the news: his asylum application had been denied. He was dropped of at a bus station in Tijuana the next day with about 300 other men, a change of clothes $143 in his backpack. He had not seen Susana since being arrested and no one could tell him where she was.

Salvador

Salvador [Note] came to the U.S. when he was 11. His family spent the next six years following the crop harvests up and down the U.S., from the Rio Grande valley to North Dakota. His parents sent him to school when they could, but more often he was in the field alongside them. He still remembered the farmer in Missouri laughing and telling him, “The Bible says, those who do not work do not eat.” He worked hard, but he remembers often being hungry anyway – though not as often as before they had crossed the border. When he was seventeen, his cousin brought him to Los Angeles to work for his construction company. He married Juana when he was 22, and their two children were born soon after. His oldest goes to school but with the youngest still needing daycare he and Juana struggle to make ends meet.

Salvador tried hard to keep his head down but the guy driving his work truck was not so careful. He ran a stop sign and was arrested along with Salvador and the three other men in the truck. At the jail, an agent handed Salvador a paper and told him he had a choice: sign or spend the rest of the year in a prison in Lumpkin, Ga. Salvador panicked. He signed. 18 hours later he was standing next to Alberto on the corner in Tijuana. Juana did not know yet that he had been arrested. They had always vaguely known that this could happen but had never managed to figure out a plan for if it did. Now he was back in Mexico with no wallet, no phone, and no idea what to do next.

[Note] Details are drawn from several migrant stories. These accounts are typical of certain migrant experiences.

Deportation – The End?

When I work with immigration clients, deportation is the end of the line. From a legal perspective, my main role is to help my clients understand how they can simultaneously avoid getting into trouble that could cause their deportation and qualify for status that protects them from being deported.

I have always understood that avoiding deportation may not be possible, or even preferable, in every situation. Some of the people we serve simply do not and will not qualify for legal status. Some realize that their best option is to return to their home country. I even believe that God can use deportation as a means of moving people who, like Jonah or the Apostles in Jerusalem, are missing a gospel opportunity through disobedience or complacency. Still, it can be hard to keep that broader perspective in mind when deportation represents both a personal tragedy and the end of a long, expensive battle for me and my clients.

After the Worst Happens

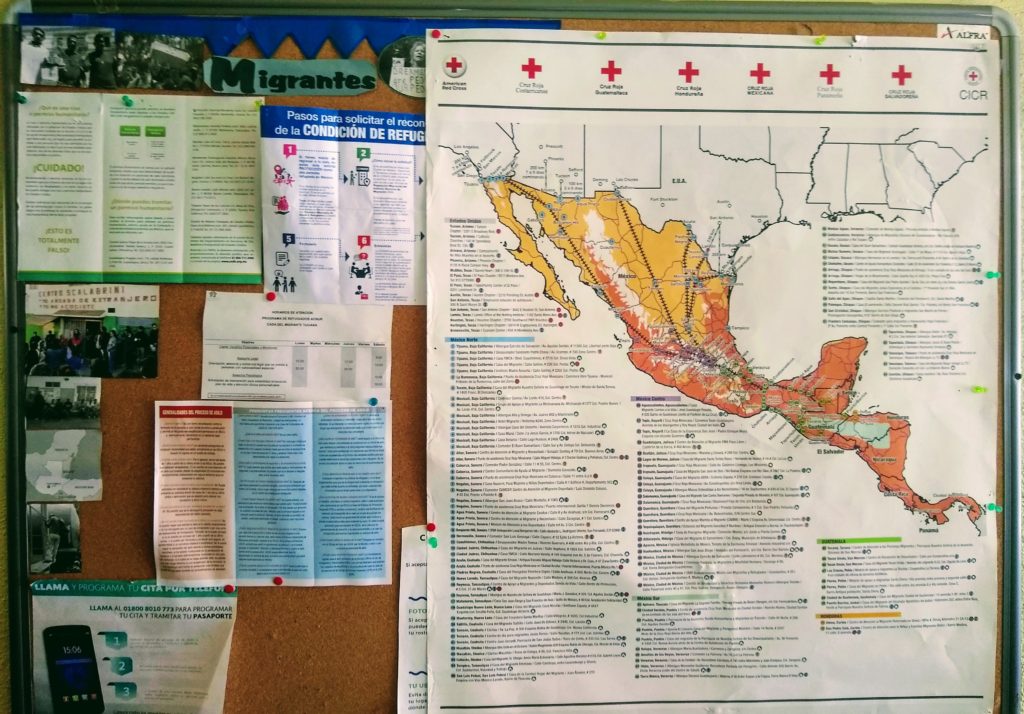

For others, though, their ministry begins at deportation. Last weekend, I visited Casa del Migrante Scalabrini and Igelsia Metodista Nuevo Pacto in Tijuana, Mexico as part of an immersion experience through The Justice Institute.

Casa del Migrante Scalabrini

Casa del Migrante is a Catholic shelter that houses migrants who recently arrived in the city. 90% of the men they serve have been deported across the nearby border with San Diego, Calif. The 20-30 men they take in each day arrive with almost no possessions and little idea of what to do next. Many have experienced serious trauma – persecution, extreme poverty, deprivation and violence as they traveled, detention and family separation – and carry the physical and psychological wounds. They will spend between 3 and 45 days at Casa del Migrante receiving shelter, homecooked meals, clothes, access to healthcare, counseling from a social worker and an opportunity to receive vocational and biblical education. The goal of Casa del Migrante is to address their urgent needs, then quickly redirect the men to make plans and take steps to ensure their future stability. Casa has contacts with employers and housing in the city. They require and coach residents to go out during the day to make contacts and find work. Former residents receive follow-up services and meals for several weeks after they leave the shelter. “Graduates from our program often send cards from wherever they get established, telling us how grateful they are for our help,” Valeria, a staff member at Casa del Migrante, tells us. “Those who settle locally may come back to volunteer, and others send packages of socks or underwear.”

Iglesia Metodista Templo Evangelico Nuevo Pacto

Iglesia Metodista Templo Evangelico Nuevo Pacto (Evangelical Temple of the New Covenant Methodist Church) is part of a broader effort by the Methodist Church in Mexico to care for those traveling the migrant trail from Central America, through Mexico, to the U.S. border. Nuevo Pacto operates one of several “comedors” (dining halls) the Methodist Church has established along the migrant trail through Mexico and the U.S. border. The church now serves a daily meal to about 600 people, mostly migrants who have recently arrived from Central America or been deported from the United States. “The best part is seeing the kids so happy,” the pastor of the church tells our group. “Many of them have not eaten for quite a while. They get a full meal, and then dessert! They have such big smiles as they leave.” In addition to feeding these migrants, Nuevo Pacto and other Mexican Methodist Churches are also advocating for migrants to be treated with humanity and dignity as children of God.

The Body of Christ

Any humanitarian crisis is an opportunity to show and share the gospel and God’s love. The light shines in the darkness, even when situations seem hopeless and people lost. Many of those involved, both aid workers and migrants, are Christian brothers and sisters. All of them are potential sons and daughters Christ died to save. Our role in the body may not be the same as theirs, but we can and must understand their pain, commend their work and celebrate their triumphs. We can also support them through donations and prayer. If you are interested and able, please look these organizations up. They are worth it, as are those they serve.